Background:

Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (“ESG”) investing is both the most significant and least understood discussion topic in the financial community today. The main reason for confusion is that there is no commonly accepted definition or approach to ESG investing. Rather, the term covers a wide range of investment goals, philosophies and frameworks which sometimes have conflicting methods and objectives. We know the terms or sub-categories of investment often used alongside “ESG” (Responsible investing, sustainable investing, impact investing, ethical investing, etc.) but what is less clear is what distinguishes one category from another, and how both asset managers and asset owners are expected to integrate these various approaches into their businesses. The goal of this blog post is to explore this complex and changing topic, analyze the potential for our industry and point out some of the major questions and challenges ahead.

The category of ethical or socially conscious investing dates back to Biblical times with various societies either restricting or promoting investment features based on their own traditions and cultural value systems. Some of these systems remain in place today, such as Shariah Law’s delineation of the responsibilities of institutions and individuals based on a philosophical relationship between risk and profit. In the United States, socially responsible investing began with faith-based factions creating investment funds as early as the 18th century. These platforms primarily resisted investing in industries such as alcohol and tobacco which crossed well defined moral boundaries for their constituents. From the 1960’s to the 1980’s the concept of socially responsible investing expanded outside of religion to address geopolitical concerns of the time such as the Vietnam War and South African Apartheid. While the development of ESG investing has varied by culture, a common thread is that the owners of capital realize both a power and responsibility in how that wealth is deployed within their society.

The re-emergence of ESG investing is really a result of a number of themes coming to the forefront of our global discourse at the same time, including: (i) increased climate and environmental awareness (culminating in the Paris Climate Agreement in 2016), (ii) societal outrage driven by a series of high profile breaches in corporate governance and transparency (Enron, Wells Fargo, etc.), (iii) a push to analyze companies based on how they impact all stakeholders (investors / capital providers, employees, customers, society at large etc.) rather than a myopic focus on rewards to capital, and (iv) a broad recognition that companies which support a culture of inclusion and a diverse set of perspectives are more successful over time.

More broadly, ESG Investing argues that traditional financial analysis imperfectly evaluates environmental, social, and corporate governance issues to the ultimate detriment of stakeholders. This imperfection is often the result of mismatches within the incentive structure of individual stakeholders or the temporal bias of their position (i.e., the friction of differing timelines between investors and other stakeholders). While many of these issues would fall into the category of “non-financial” using a strict accounting framework, ESG advocates would argue that it is often these “non-financial” issues that have outsized financial impacts if not addressed properly. By integrating ESG principles into their existing framework, investors will be able to better analyze the risks and potential strengths of their investment portfolio. From a societal standpoint, ESG adoption will over time allocate resources more efficiently, lowering the cost of capital for companies and projects which benefit from ESG considerations while raising it for those deemed dangerous.

Defining Your ESG Approach:

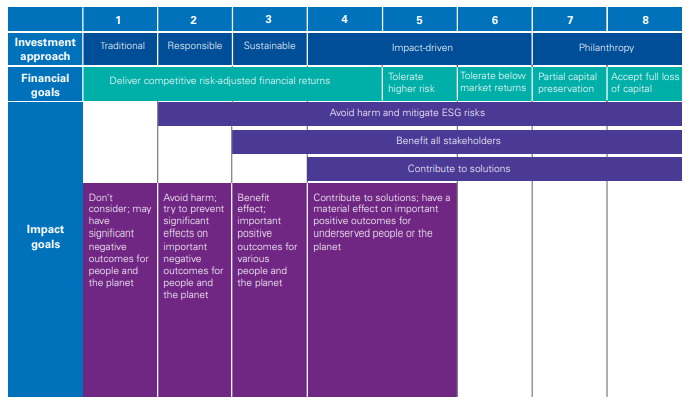

With some background out of the way, let’s look at where the rubber meets the road and discuss how the topic of ESG Investing can be practically integrated into the existing financial community. If you are an investor, you generally understand the importance of terminology and categorization (name another industry that likes acronyms as much as we do!). This blog post has already used a number of terms which may or may not go together depending on your perspective: ESG, Sustainable Investing, Impact Investing, Socially Responsible Investing, etc. How do they all relate? It is easiest to think of these approaches on a spectrum spanning from a traditional investor with no ESG considerations to a philanthropic organization driven solely by their impact targets:

A first step is for asset owners and asset managers to try and define where they fit on this continuum. Part of this process is having an internal dialogue around how they see ESG considerations impacting their investment decisions. Some key observations & questions include:

- ESG factors clearly differ by investment focus and fund structure. By most accounts, the private equity world has been at the forefront of ESG integration, in a large part owing to their elongated investment timeframe relative to other market participants. This is intuitive, as a 7-10-year investment period may value the benefits of changes to culture, governance, or environmental commitments which a hedge fund or short-term investor may have historically disregarded. Clearly, for thematic funds focused on topics such as energy or specific technologies, ESG considerations may drive the thesis whereas a purely quantitative strategy or traditional global macro fund may have trouble seeing how ESG considerations pair with their mandate and process. This is why an ESG framework for one firm may be substantially different from another.

- Is this about risk management or return potential? The two are clearly entwined but while a risk driven model may lend itself more toward screening and exclusion, a proactive approach recognizing the return potential of sectors or business models benefitting from ESG may lead to more targeted thematic investments.

- Is there a moral element to this process, and if so, how do we make sure our moral framework is representative of our stakeholders? This becomes more complicated if asset managers are investing on behalf of large populations with potentially conflicting cultural or moral values.

- If we are no longer assessing investments solely on their economic return potential how are we measuring and benchmarking ourselves? If ESG investing successfully lowers the cost of capital for certain businesses, this will have an impact on investor returns in the ESG space over time. Are asset managers and allocators willing to accept a lower return profile? How does this impact a firm’s fiduciary responsibilities?

Execution and Integration:

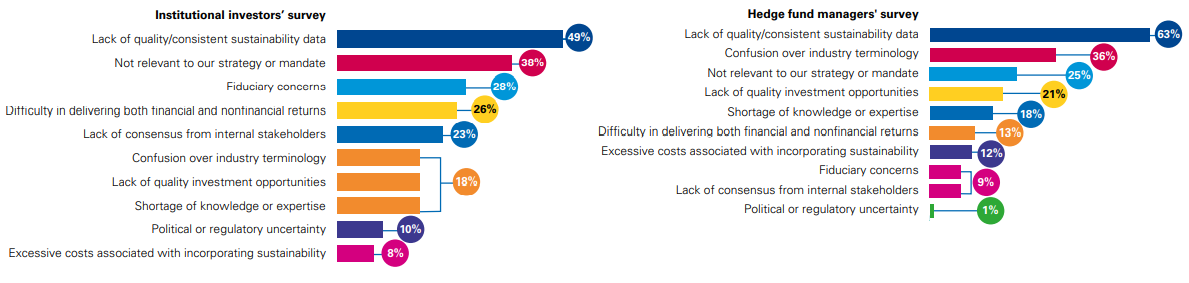

When we think of ESG investing we tend to think of the stark contrasts between industries or companies that most clearly demonstrate the movement’s value proposition (lignite coal producers vs. renewable energy, companies with poor worker protections being shunned, lack of board independence being corrected, etc.). In reality, analyzing a company’s ESG profile is typically a deep, bottom up analysis that varies dramatically by sector and, often times, region. The primary drivers for a mining company in Africa are likely completely different than those of a tech company in Europe. Additionally, the regulatory frameworks on this topic are in their infancy with major differences between Europe and the United States already emerging. Finally, “best practices” for ESG are rapidly changing with no standard set of disclosure / reporting in place globally.

With that in mind, it is no wonder that when the 2020 KPMG-CAIA-AIMA-CREATE Survey asked hedge fund managers and a broader set of institutional investors what the biggest challenges were to making ESG oriented investments, both investors sets identified a “lack of quality / consistent sustainability data” as their primary challenge.

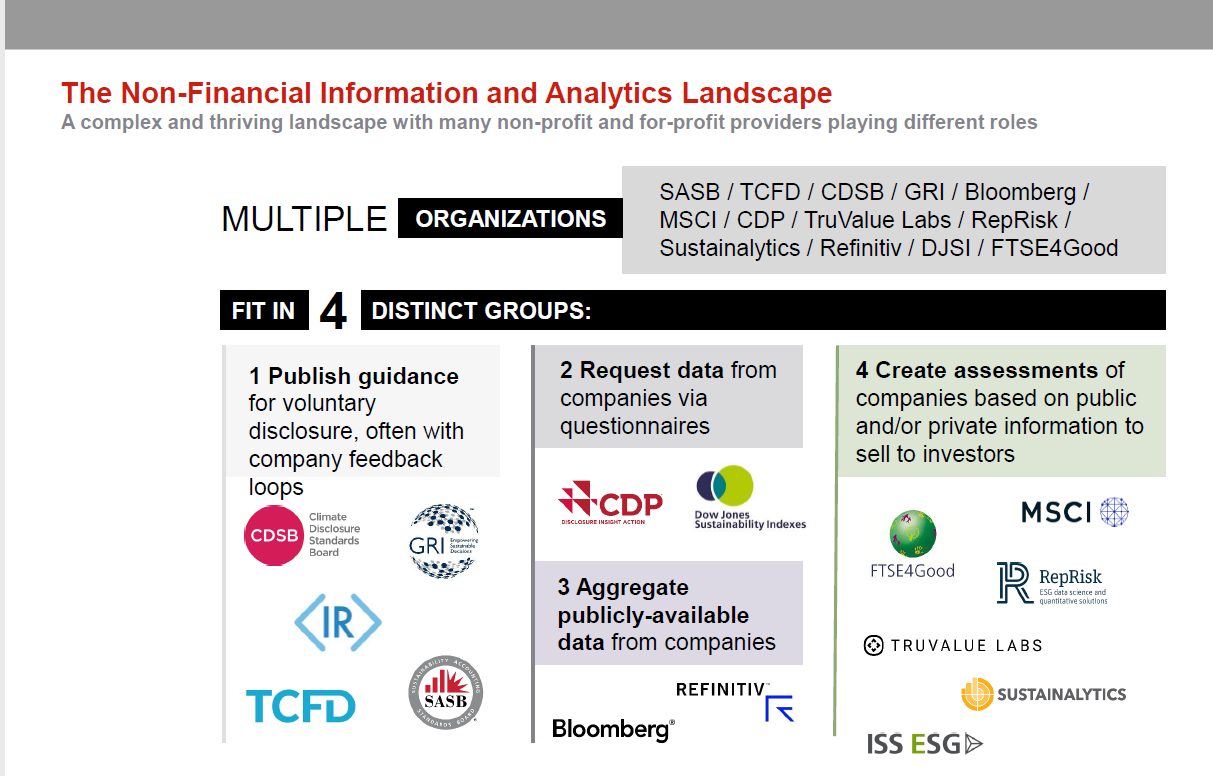

As the following slide outlines, the rise of ESG interest paired with a lack of actionable data has driven rapid growth in the Non-Financial Information and Analytics landscape:

The organizations in category 1 above focused on publishing guidance are an essential starting point for investors approaching ESG for the first time. Specifically, we have found SASB’s Materiality Map incredibly useful (a link to the map can be found HERE).

Another interesting category to focus on are groups creating assessments of companies based on their own ESG frameworks (Sustainalytics, MSCI, ISS ESG, etc.). These companies aggregate both public and private data and typically assign a number or letter risk rating which subscribers can use to assess their own portfolio. While the business case for these companies is entirely logical (concentrated expertise to assess risks – similar to a credit rating agency), there are a few potential issues we see as their influence on the industry grows. In order to analyze the different providers in this space, we conducted several discussions with rating agencies, explored their research products and methodology disclosures and reviewed third party ranking reports on the industry.

Here are some takeaways:

First, as outlined above, ESG integration should ideally be driven by an investor’s specific goals and parameters – to the extent these groups become a way of outsourcing ESG compliance, how do subscribers ensure goals and methods are aligned? There is a real risk that utilizing third party ESG ratings agencies becomes a “check the box” exercise for investors – given the quality of analysis we have seen in the rating agency space thus far, we foresee this as problematic (more on that below).

Second, while there are clearly overlaps in process, ESG ratings across different providers have shown exceptionally low correlations with one another. As UBS noted in a recent piece: “One recent study from researchers at MIT highlighted a correlation of 0.61 between 4 major ESG providers in terms of their ratings for individual securities. Significantly lower than the correlation between Moody’s & S&P of 0.99.” Part of this is driven by the fact that there is no consistent framework for reporting and data submission between providers. We have spoken to several companies who complained about the informality of reporting. Often times, companies receive questionnaires through their investor relations portal with no knowledge of the ratings providers process or track record. Additionally, given that disclosure is an important element to the ESG process, not answering or partially answering a questionnaire can have a real impact on ratings. While large corporations may be staffed appropriately to handle this process (which can require hundreds of hours and multiple dedicated employees), small and midsize companies are often not. This leads to an inherent bias in ratings from the outset based on the company’s size, budget, and personnel constraints.

Third, ESG analysis is a complex and time intensive process where the quality of the data, the rubric, and the analyst matter. While some categories lend themselves to quantification (“GHG emissions reporting”), others do not, making them more subjective / dependent on analyst interpretation (“are community engagement programs sufficient”). In interviews we completed with one top ranked ratings provider, they stated that the company covers over 12,000 companies with close to 300 research analysts in 16 different offices. That breaks down to roughly 40 companies per analyst, but they clarified that the universe is nowhere near evenly distributed. For large / mega cap companies with high news flow they may have an analyst cover only a handful of companies while small cap / emerging market analysts may have 60 – 80 names across differing sectors or geographies. While this provider’s risk ratings are formally updated annually, they are constantly interpreting news articles and corporate updates to see if they rise to the level of materiality to change a rating. Our point: Before subscribers start relying on risk ratings from external providers, they need to be sure the providers are staffed appropriately with the right skill sets.

Finally, ESG risk rating providers and credit ratings providers differ in one important way. The credit ratings business developed in order to sell securities to investors. From the beginning, corporations and credit rating agencies were aligned in their need for one another and information sharing between parties was well documented and regulated. On the other hand, the ESG ratings business arose because investors began asking for additional information which was either not being disclosed or could not be found in an aggregated format. As a result, the process of information sharing and the incentive structure between ESG rating agencies and corporates is still developing.

Because of these considerations, we believe that investors utilizing third party data and analytics providers in the ESG space should approach those services critically, constantly questioning the processes and outcomes to make sure they are aligned with their own views on the space. One interesting resource for investors and allocators is SustainAbility’s “Rate the Raters” investor survey which provides feedback on the ESG ratings industry. Here are some investor quotes from the 2020 survey we found interesting:

- “Coverage is more important than quality. The company that provides the largest coverage is typically chosen because then we can embed its data in our own investment process.”

- “There are not many ESG ratings that are useful for large asset managers — we need large universal coverage.”

- “They are the best mediocre house in a bad neighborhood… not great quality. ESG ratings oversell massively what they can do, not transparent about the problems… machine-generated reports (errors and typos).”

- “We also hear by the way that they [ESG ratings] aren’t good at taking feedback. When companies find something wrong they just say “oh sorry”… We hear that they aren’t staffed for strong support.”

- “Quality of ESG ratings is an issue. Best research and ratings are provided by investment banks (sellside) given that analysts who cover the sector have a very good understanding of companies and sectors. It is often not the case with ESG ratings analysts, who cover hundreds of companies and don’t know them well. They often do a check-box exercise, use AI, which leads to lower quality. But they still pick up some issues that our mainstream analyst can’t pick up.”

- “The main reason we don’t use ESG ratings is because we are better placed to make judgements on ESG performance than they are. Our analysts have 25 years of experience while ESG ratings providers will usually have younger graduates and have them work on a checklist of issues, which may not be critical to the way business operates and generates value.”

- “The mere concept of combining all of this different, disparate information into one score — does it make sense? You do have to understand the next layer deeper to understand the issues.”

To be clear, we are not arguing that the third-party ratings agencies do not add value. Their perspective is helpful, especially for well covered large cap companies with a developed reporting framework. In our work thus far, we’ve found them less well equipped to analyze more niche sectors or smaller, earlier stage companies.

The Curious Case of Nuclear Power:

Nuclear power and its related industries provide an interesting case study for the application of an ESG ratings framework. To begin, the topic of nuclear power tends to elicit strong emotional responses from people regardless of their level of knowledge on the industry. This is likely due to its history as a duel use technology (military and civilian) along with 50 years of propaganda from its competitors and detractors. Though an in-depth discussion of the latter point is beyond the scope of this blog post, if you are reading this, you likely know our views.

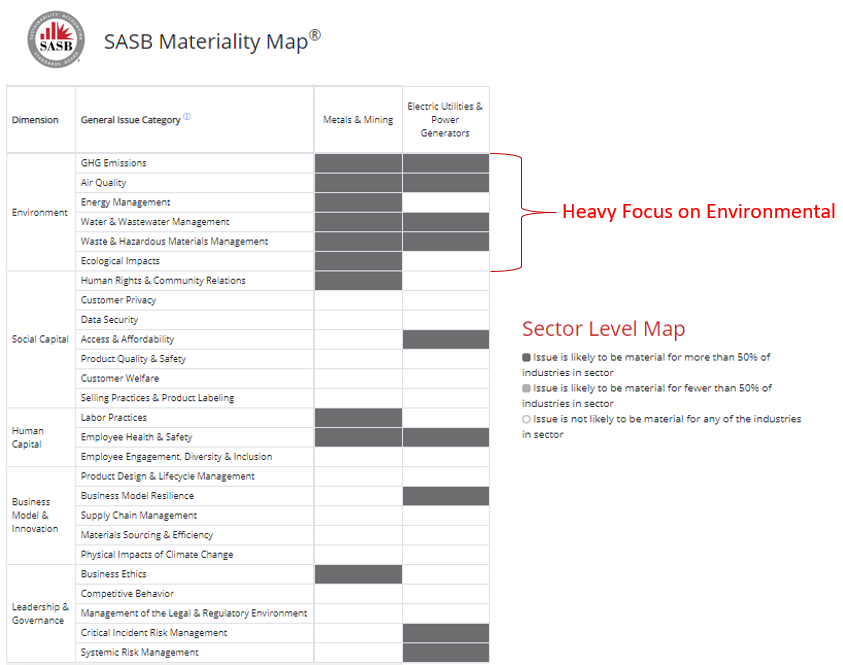

Any corporate ESG evaluation involves classifying the company’s operations and then identifying which areas of ESG analysis are most material to that company’s business model. This is where the SASB materiality map can be helpful. When analyzing the electric utilities that own and operate nuclear power plants or the uranium miners that supply fuel for those plants, you will see that the environmental component of ESG is extremely important.

What are some of nuclear power’s ESG selling points?

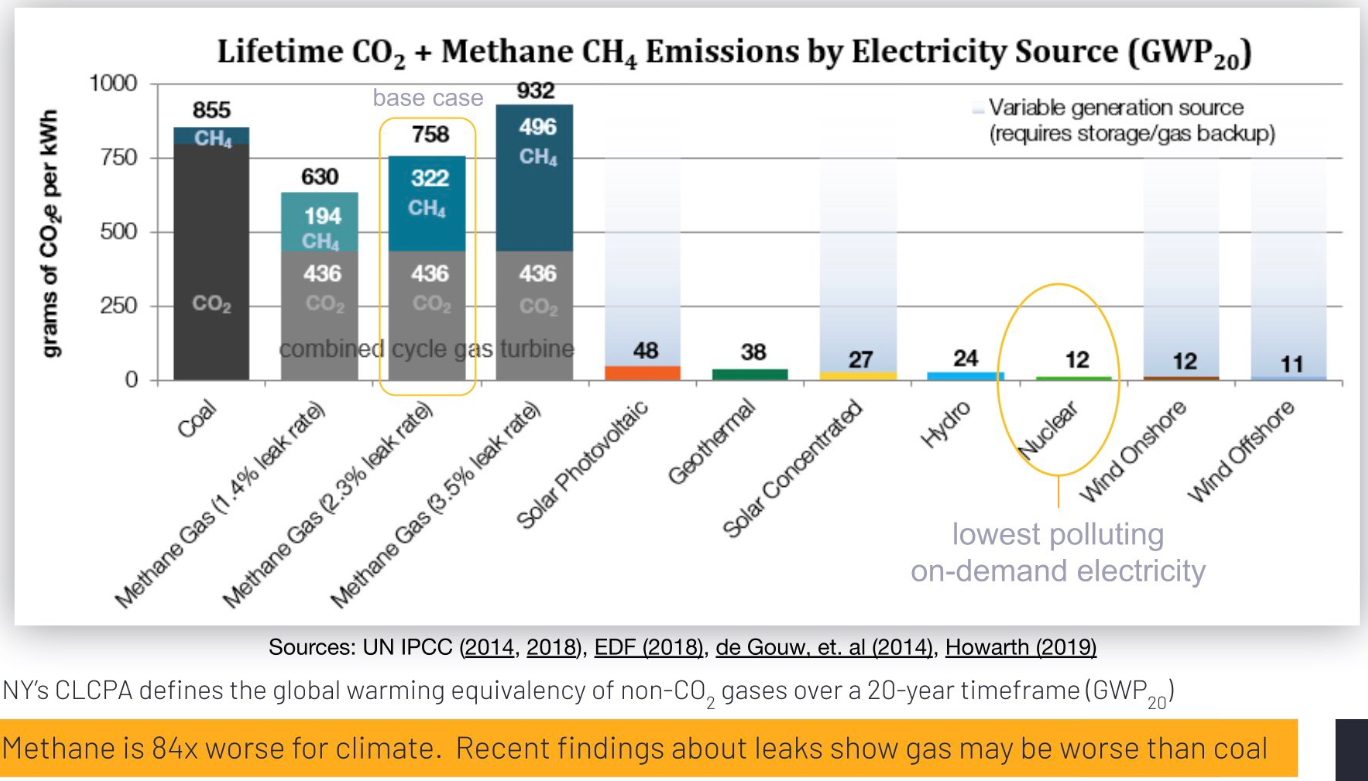

(1) Nuclear power produces lower greenhouse gas emissions than any other form of energy when taking into account the storage / backup requirements of wind and solar:

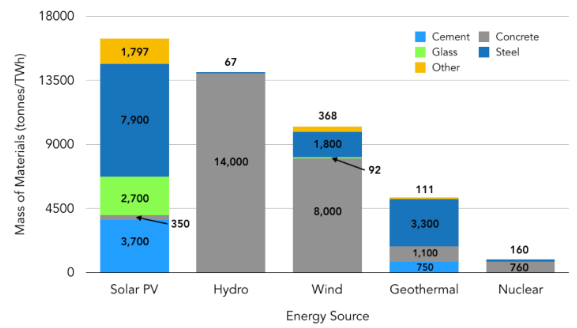

(2) Nuclear power plants have far lower materials requirements than other low carbon forms of energy, thereby lowering their lifecycle environmental impact

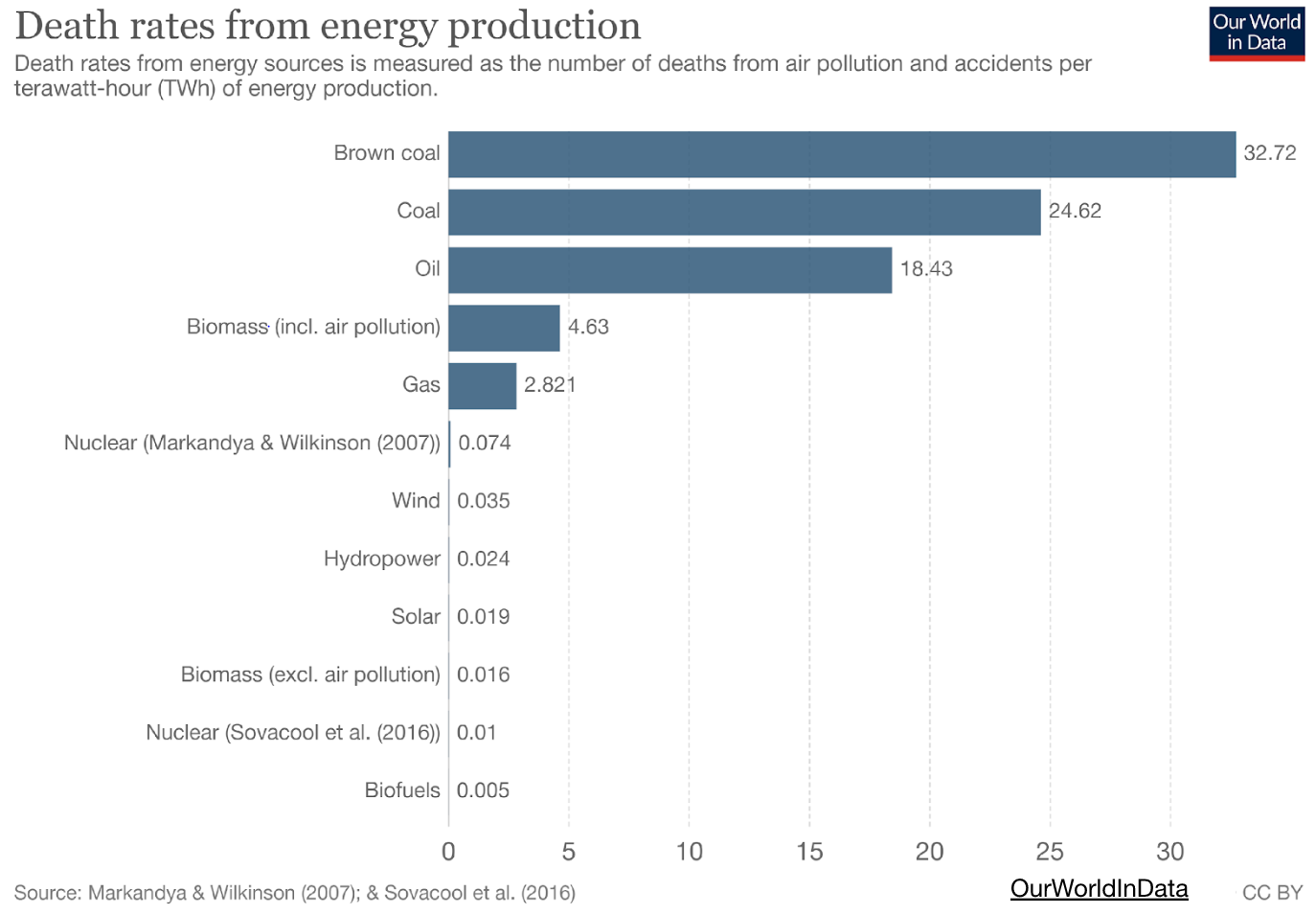

(3) Nuclear power is an incredibly safe form of energy:

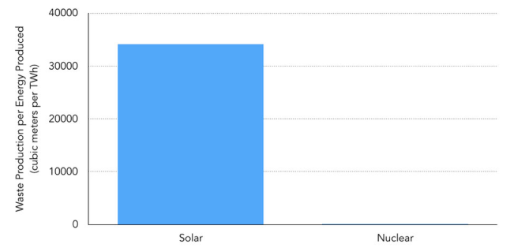

(4) While nuclear waste is often regarded as a risk of nuclear power, it is actually the technology’s main selling point. Unlike other energy sources whose waste is distributed into the atmosphere or ends up in the landfills of emerging markets, nuclear waste is fully accounted for and its costs are considered in project development (For some renewable energy such as solar, the economic and environmental cost of waste is misunderstood and likely to grow significantly going forward – as noted HERE and HERE)

In comparison, here is a photo of all the nuclear waste that Switzerland produced over 45 years, fitting in one room:

(5) Nuclear power is one of the most highly regulated industries globally with incredibly strong reporting requirements at both the corporate and international level.

(6) Worker safety and the consultation of impacted communities is a core component of the nuclear industry – from plant construction to operation to decommissioning.

While we could go on and on regarding the ESG benefits of nuclear power, it is clear that there are strong reasons why the ESG movement should look favorably on the technology and the industry. However, what we have found in analyzing various ESG frameworks is that there is incredibly little consistency between platforms. To start, many rubrics look favorably on companies which source their energy from “renewable energy” sources and greenhouse gas emissions features prominently in just about every analysis we have reviewed. So, for example, if Google purchases a certain amount of solar power it may be viewed more favorably in a rating category. Does it get the same benefit if it commits to purchasing nuclear energy? This generally varies by provider with some providers actually penalizing companies for nuclear exposure.

One specific example – we engaged with one of the largest and most well regarded ESG ratings providers to see how they addressed the topic of nuclear and uranium mining. The provider said that they do not reward or penalize a company for exposure to nuclear power in their ratings framework. However, their members portal contains a page called “Sustainable Products” where you can see if a company is involved in ESG positive practices like “renewable energy”, “resource efficiency” or “green transportation”. They also have a separate page called “Product Involvement” which seems to list ESG negative practices such as “military contracting”, “predatory lending”, “whale meat” and “adult entertainment”. Which page do you think nuclear power, a technology providing ~20% of the United States’ electricity (and over 55% of its low carbon electricity) sits? You likely guessed correctly – nuclear sits between the categories “Gambling” and “Thermal Coal” on the ESG negative page. We made some of the same ESG positive arguments cited above to the provider and they claim that those pages do not indicate the firm’s judgement of a specific industry and that the pages were generally created because clients wanted ways to flag a firm’s involvement in a controversial business. First, we would argue that users seeing the industry grouped with other clearly negative ESG categories could drastically influence investor perception of nuclear power as and ESG investment. Second, we pointed out to them that nuclear was specifically ruled out in their Sustainable Products Methodology Guide which states that “We exclude products that belong to or support industries that have a significant negative impact, such as tobacco, alchohol, thermal coal, oil and gas, palm oil, predatory lending, and NUCLEAR” (emphasis added).

John Gorman, President and CEO of the Canadian Nuclear Association and a lifelong environmentalist, stated in a great blog post last week (which can be read HERE):

“Nuclear delivers carbon-free, reliable energy 24 hours a day and has historically been one of the largest contributors of carbon-free electricity globally. Despite that, nuclear is not consistently and clearly being defined as the clean energy source that it is. That’s perpetuating misconceptions, shaping politics and hindering urgent environmental progress.”

From our work on this topic, it appears that some providing ESG ratings and guidance are furthering nuclear misconceptions rather than correcting them. That being said – this also goes to a broader issue, which is that nuclear power lacks a clear advocate and voice to argue for inclusion. As stated above, today there is no unified vision of what should and should not be considered ESG. It falls on the industry and investors supporting the industry to advocate for fair treatment with these various guidance publishers and ratings providers (if you’d like to take part in the process – please reach out to us).

Let’s move on to the mining side for a moment, as raw materials and commodities are one area where ESG frameworks seem to need the most work. A big question for ESG analysis is how far upstream and downstream your evaluation should go. Remember that one of the goals of the ESG movement is to lower the cost of capital for industries with ESG friendly businesses and raise it for the opposite. Electric vehicles are a great test case here. Most rubrics will view electric car companies favorably from an environmental side as they are part of the solution to climate change. However, many ratings systems do not extend that benefit to the mining companies whose lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese are essential for the EV market to exist. Take MSCI’s sustainable impact framework which rates companies based on, in part, the percent of their revenues associated with environmental impact. Do raw materials which are essential to clean energy development get recognized as contributing or are they disregarded because they can also be used in manufacturing stainless steel? Given that the cost of batteries is likely to be driven more and more by raw material costs over time, impacting the cost of capital for miners and incentivizing additional production should be just as important to an ESG framework as lowering it for Tesla. To oversimplify this topic – if we want the world of the future with clean energy, more efficient buildings and battery storage, someone will need to get their hands dirty mining the materials needed to create that future. If the goal of ESG investing is to incentivize that transition, maybe it’s where capital should be focused rather than have it be an afterthought or excluded industry?

The mining industry is another place where nuclear becomes a perfect litmus test. Today, the vast majority of commercial uranium production is used to power civil nuclear power plants. To see how uranium companies were graded we sent a list of ~50 tickers to one of the major ESG rating providers. Of the 50 companies, only 17% were rated. Within that set, we found that some uranium miners were categorized in general Metals and Mining while others were bucketed with Oil & Gas Producers in a subindustry for Coal. No companies were given a benefit or even acknowledgement that their products were used to produce clean energy. It is clear from this company’s rubric that whether a miner produces uranium or lithium or coal, it would not impact their rating. To us, this seems to run directly against the goals of ESG investing. Finally, while this ratings provider claimed that they notify every company of their ratings and have a dialogue as part of their ratings process, we found instances where companies were unaware of their rating and claim to have never interacted with a representative from that ratings agency. It is no wonder that these companies generally scored poorly on the disclosure sections of this provider’s rubric. The goal here is not to call out ratings agencies, but to highlight that in small niche sectors, their ratings may be unreliable, and it falls to investors to do their own diligence.

We are highlighting this topic because we believe ESG considerations will become a larger and larger driver of capital over time. We also believe that within the uranium market, fuel buyers will start integrating ESG factors into their procurement frameworks in the next few years. There are serious differentiating factors across operating uranium projects globally on this front. If one looks at the ESG push Cameco and Kazatomprom have made in their public disclosures over the last two years, you will realize its importance. When examining development projects, investors should also apply an ESG lens to their analysis. Some of the more promising projects in the space have been thinking ahead and are investing heavily in community engagement, improving governance standards at the board level, and turning to new technologies which limit the environmental impact of their projects. This is a topic Segra is already pushing with its portfolio companies and it will continue to be a major part of our capital allocation process.

Conclusions:

While a complex and changing topic, many aspects of ESG analysis should already be a part of a firm’s investing process. We would be wary of either extreme – firms that have never thought about ESG considerations, and firms that think they have it all figured out.

As a last point – we are closely watching how passive investing platforms begin to integrate ESG considerations. Index inclusions, exclusions and re-weightings can be a major driver of trading flows in a stock. To the extent index providers are using third party ratings criteria to form these vehicles, investors need to understand the underlying rubrics well, especially when events and news articles can shift a company’s ESG standing overnight (vs. traditional index drivers like free float, etc. which tend to have less event risk).

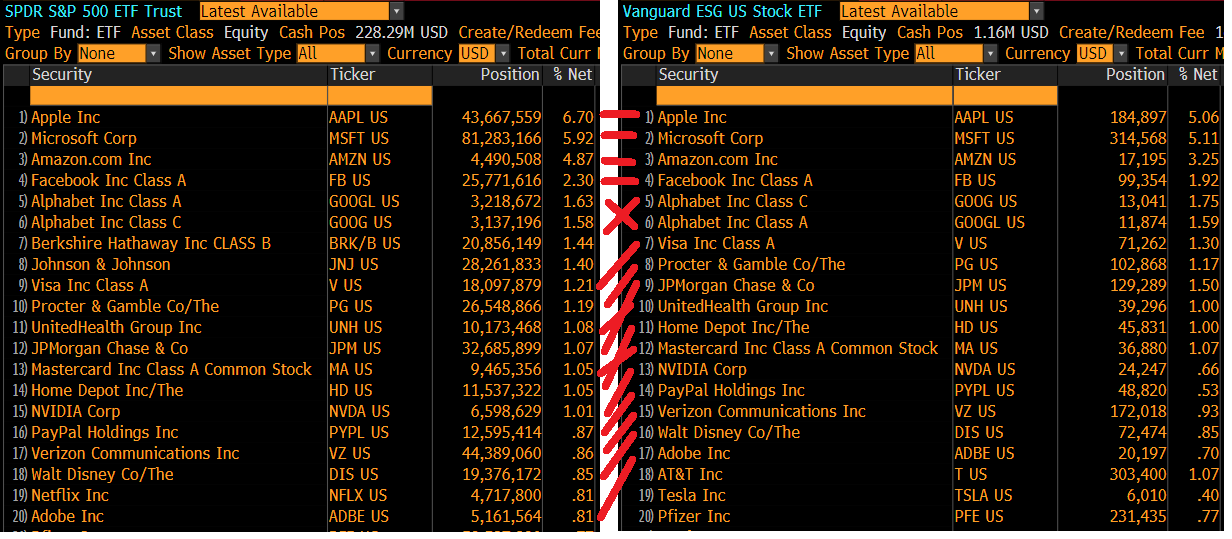

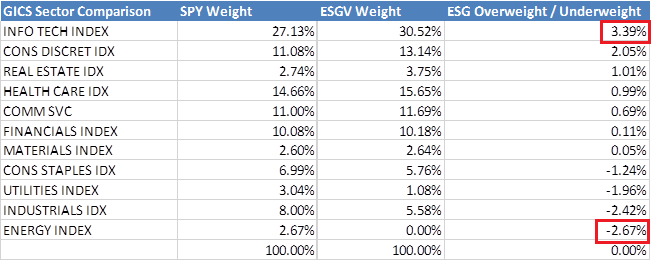

One interesting example – if you take a look at Vanguard’s U.S. Stock ESG ETF (ticker: ESGV), its top holdings are almost identical to the S&P 500. The major difference is an overweight of Info Tech and Consumer Discretionary at the expense of Energy and Industrial names. So, when articles use ESGV’s outperformance vs. SPY post COVID as evidence that ESG investing creates higher returns – make sure the return differential isn’t due solely to recent sector performance. Investors should be asking whether these products are helping them achieve their internal goals or whether they are just checking a box by choosing the ESG friendly option.

We plan to continue evaluating the evolving ESG landscape and won’t be shy in communicating updates to our limited partners and general followers.

Thanks for reading,

Segra Capital Management

[1] We won’t get into the upsteam considerations of electric vehicles here but would point out that an EV’s environmental impact is wholly dependent on grid system where it is driven so EVs in China driving on coal power are far less environmentally friendly than one might think!