Disclaimer: Nothing that follows is investment advice. Please see our “Terms” page link below for more information regarding this website.

The single question we are asked more than any other: “how much material is there in the spot market?” This question has been prevalent since we founded Segra Resource Partners in 2018 but has become THE topic of most of our discussions with market participants, limited partners and sell side analysts since Sprott Asset Management’s takeover of Uranium Participation Corp this summer to form the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (“Sprott” or “#SPUT”, Bloomberg ticker: U-U.CN).

Unfortunately, our answer to the question begins with “well, that depends” and proceeds to dive into a long and detailed discussion of how the physical market for uranium actually functions which differs drastically from the picture many “experts” have been painting recently on social media. The purpose of this Blog post will be to explain our take on spot market dynamics and how they have been impacted by #SPUT. We’ll explain where the pounds are likely coming from, the knock-on impacts to mining companies, how the trust is likely to impact this commodity cycle and outline a few things to watch going forward.

The birth of the #SPUT has clearly had a powerful impact on the uranium market, with the spot price increasing over 50% to $47 from its August low of $30. Since the acquisition, Sprott has purchased over 21 million pounds, growing assets under management to close to $2 billion. We’d note that much of this move has happened with utilities on the sidelines, largely surprised by a $15-20 jump and hoping that Sprott is a short-term phenomenon that can be “waited out.” We don’t believe that’s likely to be true and expect utilities to feel Sprott’s impact, not just in the spot market but on their their mid- and long-term contract books as the cycle progresses (they are connected – as we outline below). We’d remind readers that we’ve always said the real fun begins when utilities re-enter the long term market in force.

While this type of growth and momentum is clearly a huge success for the folks at Sprott, many investors have been surprised by the amount of material they have been able to buy in a relatively short timeframe. The questions that follow are logical: Where are they getting the pounds? How many more are out there? Is this a question of mobile vs. immobile inventories? Would these pounds be in the market if Sprott wasn’t buying? When does uranium get to $200 – the articulate gentleman on twitter told me it would, and I’ve been waiting three whole months!?!?

Buckle up because there’s a lot to unpack here…

Spot Market Basics

To start we’re going to run through some uranium spot market basics for those new to the industry. First, unlike some commodities, the spot market for uranium is defined as any material purchased for delivery within 1-year. This is different from many other commodity markets in which the term “spot” means for immediate delivery, as opposed to purchases 1, 3, 6 or 9 months out. This is important because you can purchase “spot” uranium for delivery in October 2022 today and the pounds may not even be mined yet! For that reason, many market players will differentiate between buying “pounds in a can” which are above ground at a conversion facility (or in transit) and those farther out the curve.[i]

Another key dynamic is that traders and financial intermediaries play a major role in this market resulting in a complex web of counterparty obligations (and risk) which is very difficult for outsiders to analyze given the bespoke, bilateral nature of contracts.

A few roles intermediaries play in uranium:

- Allowing for off balance sheet financing of material (the famous “carry trade” – more on this later)

- Arbitraging spread differentials between delivery locations or fuel cycle forms (trading between U3O8, UF6, EUP etc.)

- Managing counterparty credit risk for producers and end users

- “Sleeving” material between counterparties to achieve a targeted market impact (let’s say you want to sell material, but you don’t want to be seen selling material – a trader can give clients anonymity when transacting in the market)

It is important to understand that the role of traders and intermediaries is not static – it is dynamic and constantly changing with the market. Said differently, the role of a trader or intermediary is not to drive the market in one direction or another, but to react and adapt to what the market is giving you at any point in the cycle.

So back to our initial question – how much material is in the spot market?

ANSWER: It depends on the following factors: the spot price, the shape of the forward curve (often, but not always driven by interest rates), the availability of primary production at various prices and points in time, trader positioning, and inventory levels. The spot market does not exist in a vacuum – there are not a defined number of pounds in the spot market at any given time. Instead, material flows into and out of the spot market driven by the factors cited above.

Primary Production and Inventories

When most people think of spot market supply, they focus on two sources – primary production and inventories. Primary production is the simplest source of supply in the market to understand and is often used to estimate market depth. While the majority of uranium production over time has been sold via mid- and long-term contracts, there will always be a certain amount of material which is sold into the spot market. Sellers have a variety of motivations – they may be selling uranium produced as a by-product of a broader mining operation which makes them price insensitive, sellers may outsource marketing to a trading organization and be less price focused, they may be selling on behalf of an organization that is not a traditional market participant (for example, a government’s share of production in a mine). Regardless of motivation, you can think of this supply as relatively inelastic and predictable (i.e., it doesn’t fluctuate based on prices or which market participants are buying). While some portion of Sprott’s purchases have inevitably been from this category, it is unlikely to explain the majority of recent volumes.

Inventories are somewhat different and harder to estimate. For most utilities, inventories can be divided into strategic and non-strategic, with the latter being often referred to as discretionary. Price can have a significant impact on inventory management and this inventory buying or selling will help drive the spot market. Given the opaque nature of the market, it is impossible to tell exactly how inventory management has changed as a result of the recent move in prices. A bearish take would be to assume that as prices have risen from $25 to $45, market participants have sold down inventory to take advantage of higher prices. While we can’t rule that out entirely, we don’t think it’s been a big portion of recent spot supply – lets walk through why.

In many markets inventory management is a countercyclical element which helps smooth out the price cycle. This is intuitive – why not stock up on something you need while prices are low and draw down that inventory which prices are high? If history is any guide, inventory management for uranium is actually a procyclical factor. Without re-hashing much uranium 101 – compared with other electricity generation options, fuel (uranium) is a relatively small portion of your total energy cost for nuclear power. However, nuclear power plants are meant to run at high capacity-factors, meaning that fuel related outages are very costly for a utility. Because of this, fuel buyers have historically increased inventories when they are nervous about securing supply even if it means they are doing so at higher prices. Another way to think of this – the value of uranium is driven more by availability than by price (i.e., it is a scarcity driven procurement cycle, not a price driven one) so inventory management typically adds volatility to a price cycle rather than dampening it. An overly simplistic analogy – you may not stockpile bottled water in your basement every day, but if a hurricane was coming you likely would. When you buy water ahead of that storm you are doing so out of necessity – almost regardless of price, you cannot run out of water. At these times, scarcity (or perceived scarcity) drives procurement, rather than price…

OK, fine but how are inventories impacting today’s market?!?

If you go down the list of market participants, we can’t find a smoking gun. First, producer inventories are at or near cycle lows and several producers are spot market buyers to replace production currently on care & maintenance. At the utility level, while U.S. and European inventories remain slightly above historical averages, we would make two observations – first, while regional aggregates are often reported, inventory levels can differ drastically by utility. We know at least one fuel buyer who was proactive during the bear market and is covered out to the end of this decade while we know several others who will be forced into the market in the near future to replenish fuel requirements in 2022 and 2023. Second – we’d remind readers that this will never be a low inventory, just in time market. Most utilities will at bear minimum want one core reload going through the fuel cycle at any given time (most plants are running 18-month cycles so that’s ~1.5 years of inventory) and in many places a minimum level of inventory is required from a regulatory standpoint. More broadly, our high touch conversations with utilities and traders show no indication that western utilities have used the price move to trim inventories – if anything we are hearing they are more likely to increase discretionary purchases as a result of the move.

However, there are two large pools of inventory that bears always reference as potential market overhangs – Japan and China.

I won’t spend too much time on the history behind Japanese inventories but suffice to say they are well in excess of historical levels. After Fukushima, Japanese utilities kept taking delivery of very highly priced contracted material despite having the majority of reactors offline for the decade. This resulted in an inventory of approximately 100mmlbs. Over time small amounts of Japanese inventory have found their way into the market periodically through traders but the amounts have not been significant. The majority of inventory is held at cost on the balance sheets of Japanese utilities rather than marked to market meaning that a sale would lead to a loss recognition (potentially impacting leverage requirements). Additionally, most of these utilities still have reactors in some stage of re-permitting and/or restart. They realize that taking significant losses on fuel sales while lobbying for government support and social license is unlikely to be a winning strategy. Finally – at the government level we continue to see a recommitment to long term energy targets which include nuclear energy in Japan and view their alternatives as limited. While some material may become more mobile at significantly higher prices (a large portion of contracted material was purchased in the $80-120 range), we find it unlikely that Japanese utilities who have owned this material for a decade will suddenly about face when prices have risen $15-20 and our market intelligence has not pointed to the Japanese as sellers.

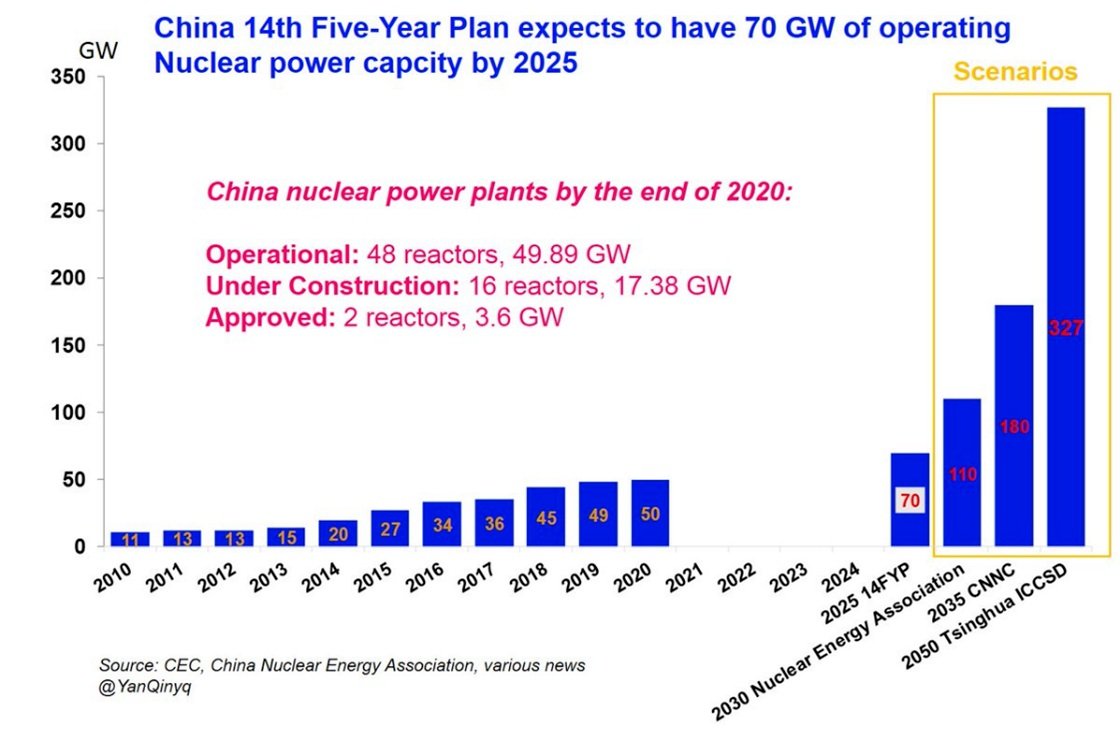

China is an interesting topic. The Chinese are in the process of the most successful nuclear buildout of all time. After a multi-year newbuild hiatus as the country transitioned to a new generation of reactors, the CCP recommitted to a national build program centered on domesticated reactor technology and continued investment into their nuclear fuel cycle. While Chinese inventories may seem large when compared to current consumption levels, they are actually quite small in relation to the country’s newbuild plan.

To us, China’s long-term plan for nuclear has as much to do with energy security as it does with decarbonization. Those outside the industry often forget that France’s nuclear buildout in the 1970’s was driven by the energy crisis rather than carbon concerns. For a government largely dependent on energy imports, the ability to stockpile 5+ years of fuel onsite for relatively low costs is a key nuclear selling point for the Chinese.

We largely view current Chinese inventory levels as strategic in nature and unlikely to be sold into a rising market. This is all the more important given the market’s adverse reaction to the recent YellowCake PLC capital raise. To briefly summarize, YellowCake PLC recently raised $150mm to buy 3 million pounds of uranium, 1 million pounds from Kazatomprom and 2 million pounds from Curzon Uranium Limited (a well-known uranium trading company). The market was spooked by the following line:

“Curzon is sourcing the U3O8 from CGN Global Uranium Limited (“CGN”), who has agreed to deliver the U3O8 directly to the Company’s account at Cameco’s Port Hope / Blind River facility, with delivery of all the U3O8 purchased from Curzon to take place before the end of November 2021”

Many market participants viewed this as evidence that the Chinese were willing to sell material into the market and were making a call on uranium prices. While the Chinese have done exactly that with other commodities in recent times in an effort to cap commodity inflation, we don’t believe that is what happened in this case. Our view is that these pounds were likely sourced via a pull forward of a carry trade already in place in the market (more on that below). While we often see the Chinese in the market as buyers and sellers, we attribute most of that activity to their trading businesses and have seen no evidence of a willingness to draw down national inventories, much less sell them. In fact, just last week Kazatomprom and Chinese announced a series of term contracts – the first time the Chinese have entered the term market in years and a sign they are buyers rather than sellers today.

The Spot Supply No One Talks About

While most investors associate primary production and inventories with the spot market, there are many other ways material can end up there. Today we’re going to walk through three such sources which have been (and will continue to be) impactful to Sprott’s purchasing program.

Trust Unit for physical material block trades

While the uranium equity bull market started in 2020, there has been financial interest building in the sector since the physical market bottomed in late 2016. It was difficult to tell exactly when the market would begin to turn but with a commodity trading a third of its marginal cost of production, several hedge funds and other financial players started to see value in the physical commodity well before equities turned north. While not large positions relative to the broader uranium market, these funds began to buy physical uranium in 2017 and 2018 and store it at converters. At the time, Uranium Participation Corp and later YellowCake were relatively illiquid vehicles – fine for retail or family offices, but difficult to trade and build an institutional position in. Additionally, there was no guarantee that buying equities in either vehicle would necessarily impact the physical market. For funds looking to go long, the logistical hurdles of actually owning the physical commodity made sense (We always used to say – if you want to buy $50k of uranium, buy UPC but if you want to buy $50mm set up an account at Cameco).

The problem with owning physical uranium is never on entry – it’s finding an exit that doesn’t disrupt the market. If you look at the last cycle, hedge funds and other financial players were quite active in the market during the bull run – the problem was that when they started selling, everyone knew how many pounds were coming back into the market. You can count the number of active players in this market on two hands and they all talk. If you are the new guy who bought 2 million pounds last year, you should just assume bids will evaporate after you try and sell your first 100,000 pounds (note – savvy funds will game that exact dynamic, but that’s a topic for another day).

Enter Sprott – now you have a vehicle which is highly liquid and has a direct translation mechanism to the physical market when trust units are purchased. If you were a hedge fund with pounds sitting at a converter, wouldn’t you want to exchange your material for trust units and gain anonymity if / when you decide to exit? That swap is a no brainer – especially if Sprott isn’t asking for much in return for the liquidity their structure provides.

This is our first source of material – Hedge Funds and other financial holders of material swapping stored pounds for trust units. There have been many times over the last few months where we saw large block trades in Sprott and significant “stacking” of material without much market impact. You may have seen bids and offers relatively stable but somehow Sprott was able to buy 750,000 pounds in an afternoon – how? The answer is that in many of these instances Sprott is not actually buying in the open market – they are exchanging trust units for physical material held by funds.

What are the implications of this? Bullish or bearish? Let’s start by just saying that every pound Sprott buys is positive for the uranium thesis – full stop. It does not matter where the pounds come from – it matters that they are going to be sequestered from the market (Won’t go into detail on Sprott’s structure but we believe they have been very clear on this). Would buying in the open market put more pressure on pricing than swapping material with funds? Of course. But Sprott’s goal is to grow the vehicle – sometimes they will do this in the market, other times they will do it off-market. What’s key is that the pounds previously held by funds would be coming back at some point (at some price), no matter what. Better to have them sold into Sprott than way on the broader market later.[ii]

Contract structures and flex options

Next – lets walk through how utility contract books may be impacting the amount of material in the spot market. The structure of contracts is often over-simplified by commentators – price, term, size. In reality, these are bilateral, bespoke agreements that differ by entity and also carry many bells and whistles which investors cannot see and rarely understand. Market related contracts may carry caps and floors on pricing. Utilities may have certain “outs” in the event of a reactor shutdown or limitations on a material’s origin. These terms also fluctuate with the cycle – at the top of a bull market, producers are able to extract far more attractive terms in exchange for parting with scarce material. At the bottom, utilities ask for optionality as producers try to retain market share and grow their customer base.

Today, we are coming out of a long bear market. During the last half decade, many utilities have been able to ask for contract terms which give them optionality and flexibility at a relatively small cost to them. For example, some contracts include a “flex” option which allows the utility to increase (and in some cases decrease) the amount of material delivered in any given year. If you pair that with either a fixed price contract or a market related contract with a cap & floor – they begin to look an awful lot like call and put options on physical uranium. For years traders and hedge funds have been active in the market looking to harvest that optionality and, in some cases, monetize it for utilities (in fact – many articles have recently referred certain large funds as “long uranium” when in reality they have been active in the physical market for years in a much more nuanced way). What you effectively have here is an options market that is completely inefficient – there is no vol surface, there is no market-maker, and the optionality has many times been given away to end users for very little.

When markets are steady, there isn’t a lot of value in these options – many of the caps for example may have been in the $40s while we fluctuated in the mid $20s for several years. However, when a large price movement happens, you suddenly have optionality very likely “in the money”.

Let’s walk through a theoretical example (over-simplified for illustrative purposes):

- A Utility signs a 3 year 1-million-pound market related contract in June 2018, at the time the spot price is $23 and the 3-year forward price is $27

- The producer asks for a Floor of $20 in exchange for a ceiling of $40

- The Utility asks for a flex-option of 20% meaning that they can ask to receive either 1.2 million or 800,000 pounds at the time of delivery.

If prices range between $20 and $40, nothing material changes. The utility may flex up or flex down that delivery based on their market views, inventory needs, etc.

However, things get really interesting when price volatility increases. If prices spike to $50 there is now real value in that flex option. The utility may only need 1 million pounds in 2021, but they will inevitably flex up their delivery as there is an easy $2 million on the table (market price of $50 – $40 cap cost x 200,000 pounds). They will then sell the extra 200,000 pounds to Sprott in the market (either directly or sleeved through a trader).

So how does this impact each market participant:

- The producer shows higher sales than they otherwise would (sales book gets flexed up vs. base case)

- The utility has effectively “found money” of $2 million (as it is unlikely they were pricing this optionality on a running basis)

- Sprott has purchased an extra 200,000 pounds, effectively from a producer

Now this is clearly an oversimplified case, and we would be remiss if we did not point out that the flex option in other cases may be having a different impact. Let’s say you are a utility with the same flex option but no cap in place – you may actually flex down your delivery to limit the recent price spike’s impact on your budget this year. Our broader point is that these contract details can actually have a relatively significant impact on spot market material when prices move dramatically. You can imagine a similar dynamic with a utility that locked in 5 year forward fixed pricing in 2016 (their flex is almost certainly in the money today).

Carry trades – “there and back again”

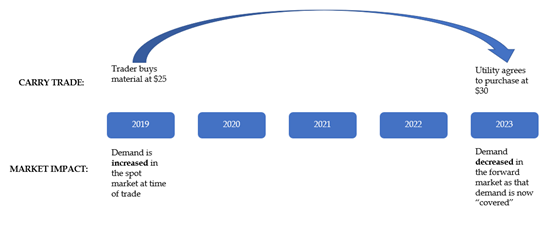

Finally – lets walk through carry positions, why they exist and how they impact spot. You can think of the most basic carry trade as an off-balance sheet financing agreement between a trader and a utility. The basic steps are as follows:

- Utility commits to buy material at a predetermined price on a future date

- Trader acquires those pounds in the spot market today and agrees to “carry” them on their own balance sheet until the delivery date

- At the delivery date pounds are delivered in exchange for funding

Under this simple agreement utilities receive committed material without having to tie up balance sheet. In exchange, traders get a guaranteed return on capital deployed with what are generally well rated credit counterparties. Seems simple – why have traders gotten such a bad wrap for providing a market service?

Carry trades are actually a function of market dynamics – in an oversupplied market where there is excess spot material, it is often cheaper to buy material today and carry it than to pay producers to mine it in the future. This means that traders are actually competing with primary producers out the curve. This is problematic for two reasons – first, producers actually want to sell most of your material out into the future (mid- and long-term markets). This is because a committed sales book de-risks your asset base which allows you to make long term capital investments. Mines are long-lived, capital-intensive assets and producers often need to make capital allocation decisions far before realizing the benefit of those investments (for example the Kazakhs budget Capex for production 2-3 years out and Cameco will likely need to decide on Cigar Lake Phase II 8-10 years prior to production). Producing and then selling into the spot market is a terrible business model over time and generally leads to boom/bust cycles which are bad for both buyers and sellers. Second, by filling demand in the midterm market (generally 2-5 years out), traders have lulled utilities into a false sense of security. If I were a utility who could relatively easily source material from both producers and traders over the next 3-4 years, should I really be worried about market balance close to a decade away? This dynamic is exactly what sets up for a market rationalization moment as oversupply turns to undersupply.

For these reasons, it is broadly understandable that traders and the carry trade have drawn the ire of investors over the last several years. However, lets be clear that traders also helped play a key role in balancing the market. If spot had remained oversupplied and traders had not purchased pounds in order to form carry trades, who knows where spot prices would have gone in the depths of the bear market. While the carry trade is blamed as a source of supply in the midterm market, it is very rarely commended for being a source of demand in spot.

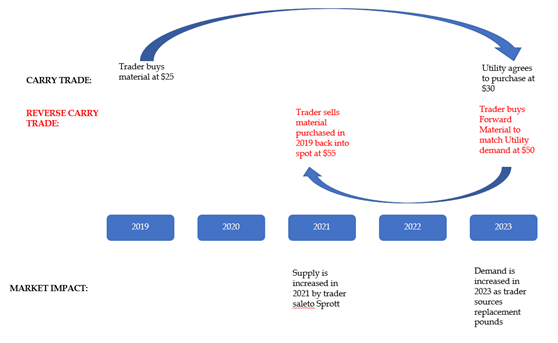

Why the long-winded introduction on carry trades? Well – as the cycle progresses, we believe reverse carry trades will play a major role in the market and the knock-on implications of this for producers and utilities could be dramatic. If a carry trade brings demand forward into the spot market at the expense of forward demand, a reverse carry should do the opposite. Let’s walk through a quick example of how this would work:

- A trader and a utility entered into a carry trade in 2019 where the spot price was $25 and the utility agreed to buy the material back from the trader in 2023 at $30

- Suppose that today the spot price is $55 and the midterm price is $50

- If the trader can secure material at $50 in 2023, he can deliver that newly purchased material into his carry trade with the utility. This will free up the material he is currently holding on his balance sheet which he can then sell into Sprott in the spot market.

- The utility still gets the material they were promised in 2023 and the trader takes advantage of the backwardated forward curve to profit from market inefficiency (as well as freeing up balance sheet)

- Lets also note that if producers were smart they would try to keep that offer as close to spot as possible in the midterm market to maximize value capture. So whether spot is $55 like this scenario or $65 or $75, they should be walking the offers up in line with the market, perhaps a dollar or two lower to create trader incentive – this is what we expect to see as these trades continue.

So how does this impact the market and market players?

First – this is phenomenally good for current producers. Every trader buying to reverse a carry trade is a new customer in a midterm market that is largely viewed as “covered” by many consultants and utilities (2022 – 2024). The more Sprott buys, the more the likes of Cameco and Kazatomprom are able to build their forward sales book and de-risk their asset base. One way to think of it – if traders compete with producers as forward sellers in a carry trade, they also compete with utilities as buyers in a reverse carry. This only happens if you have a relatively price insensitive buyer in the spot market who is willing to push the curve either flat or into backwardation (thank you, Sprott!). So from now on when you see a trader selling into Sprott, don’t take it as bearish – he may be competing with utilities to buy out the curve which is what investors have wanted all along.

While utilities are likely not spending much time on this dynamic, the impact on them later this decade may be quite severe. Every pound sold to Sprott as a result of a reverse a carry trade is one less pound which will be available to utilities down the road. What people often forget about contracting cycles is that contract value tends to be created at cycle extremes. These producers are building a layered portfolio of contracts over time. As a commodity flips from surplus into deficit, producers often initially remain focused on de-risking their asset base and, as a result are less focused on price than they are on volume. At this point in the cycle, you see producers opting for market related pricing with protective floors and fixed pricing, where utilized, may be done with the intention of building, or retaining customer relationships. However, once an asset base is relatively de-risked and a feeling of scarcity returns to the market, producers flip to profit maximization and become incredibly price focused. Market concentration (often forgotten during downturns) exacerbates this as pricing power returns with a vengeance during times of undersupply. This is exactly why you see the Chinese returning to the long-term contract market now for the first time in years.

What does this mean for Sprott? Their heavy lifting is effectively subsidizing the forward books of producers. This vehicle is a best-case scenario for Kazatomprom and Cameco. Over time it is not necessarily a bad thing for Sprott – the forward market will be far tighter than it otherwise would be which will result in higher prices. However, market participants should know that at the right price, with the right curve shape there is actually a lot of material that will flow back into the spot market. How much? Well, that depends to a certain extent on trader’s ability to source forward material and reverse a carry (contrary to popular belief, traders are not in the business of taking short positions in this market) but there are easily tens of millions of pounds on carry today so the volume will likely be significant as the cycle progresses. As long as producers are willing to sell forward into the market, the mid- and long-term price will serve as an anchor to the spot market (as a steeper backwardation brings more and more material out of the midterm market and into the spot market). Think of this when you read a boozy Saturday night twitter thread calling for $500 uranium and outlining how the spot market is running out of material (hint: it’s not, but the long-term market might be).

We’ll touch on one more dynamic at play which readers may have heard about. In today’s market sellers are sometimes offering spot material at a discount to utilities because they are viewed as end-users. So, for example if a utility approaches a seller, they may be offered $46 when the quoted spot price is $48 for intermediaries and financial players. This is not uncommon, and the logic makes sense – discount material that you won’t have to compete with again in the market and sell the expensive material to the investors. The problem is that (contrary to popular belief) utilities are very sharp and understand that there is an arbitrage. For this reason, you may see utilities buy material at $46, sell it to a trader who will then push the material back into the spot market at $48 hoping to split the spread. We don’t think this is happening in significant size (as utilities are not traders and typically are not putting balance sheet at risk for short term profits) but we do think you will see the larger, savvier utilities do this at the margin and it will contribute to trader churn.

Why isn’t anyone talking about all this?

While much ink has been spilled on Sprott this fall, we have been surprised by how unwilling most investors and reporters have been to dive deeper into market structure and find out what is actually going on. Why aren’t market participants raising these points to counter these absurd twitter threads? The simple answer is that it is easier to fool people than to convince them they have been fooled.

Our goal with this rather longwinded post is to warn investors that much of the rhetoric dominating the sector of late shows a fundamental lack of understanding for how this market actually functions. Uranium remains and incredibly opaque, complex market (we have followed the market on a dedicated basis for years, have much better access than most others and still learn something new most days). We understand why the loudest market participant often gets the most attention but would caution anyone from putting capital behind a carnival barker promising you the moon.

Misinformation in today’s market

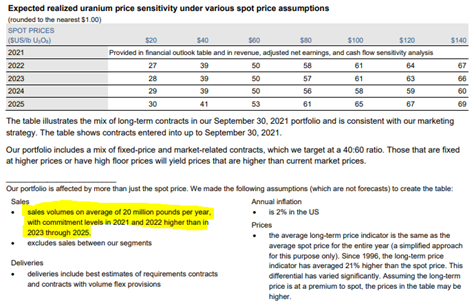

Recently there has been much discussion over whether Cameco is in fact “short the market” and whether a rising spot price could jeopardize their business. This argument is ludicrous, and we have been shocked that it has gained so much traction on social media (this tells us the market remains less efficient than one might despite recent performance). The short argument is basically that because Cameco’s forward contract book is larger than current production, they will be caught in a short squeeze as prices rise. This seems to have been driven by Cameco’s price sensitivity and cashflow tables in their quarterly financial statements which indeed do show that Cameco’s current contract book sees relatively limited upside from spot process above $80 dollars per pound:

The theory goes on to state that because McArthur River will take time to ramp up, any short-term spike in prices will force Cameco to panic buy in the spot market, having significant knock-on effects to the company’s earnings, cashflows, leverage and credit ratings. The proponent of this thesis has even gone so far as to say that a rise in spot prices could push the company into default and bankruptcy (oh my!).

What the bears are calling “short” Cameco would refer to as “over-contracted” (they reference it as a core corporate strategy in every earnings call). If you look back, they have had contracts outstripping their production base for most of the last decade. This approach has allowed them to purchase in the market and help managed the cycle. This has had a clear impact on market rebalancing and created real value for shareholders. The opposite – overproducing without committed contracts, is what got the industry in this mess in the first place and exactly what destroys shareholder value over time. Suffice to say, we don’t think the short argument holds water as the company has strategically placed themselves in this exact position and has a number of levers to pull as the market (by design) tightens.

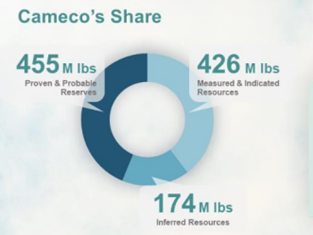

I’ll go through some basic numbers to show how flawed the short argument is but let’s just start with this one – Cameco currently has approximately 1 billion pounds of Reserves and Resources across its asset base vs. a forward contract book of 75 million pounds in committed sales (between 2022 and 2025). For some reason the short side seems unable to piece together that Cameco is in fact long those unsold / uncommitted pounds (optimizing pricing for which is the whole reason they have exercised restraint and kept ~114 million pounds underground on care & maintenance since 2016). The sensitivity tables that seem to be the core part of this argument only include the current contract book which is a very small portion of the company’s overall asset base. Now, at $25 uranium one could argue that those assets may stay in the ground permanently – what we can’t understand is why someone arguing for $200 uranium wouldn’t see those pounds as assets given all of them could be mined quite profitably at those economics.

But perhaps we’re not being fair. Maybe it’s a timing issue – in his mind spot prices will spike to $200 imminently and Cameco will be caught short in the time between now (or when its contracts are due) and when they can get ramp up production.[iii]

Let’s walk through the basic sources and uses:

As outlined above, Cameco’s contract portfolio is “on average 20 million pounds per year over the next 5 years with commitment levels in 2021 and 2022 higher than in 2023 – 2025”. Cameco’s sales guidance is 23-25 million pounds for 2021 of which ~18 million pounds had been delivered as of 9/30. So rough numbers, Cameco needs 75-78 million pounds of uranium between 2022 and 2025 to meet contractual obligations.

Cameco can meet those contractual obligations in several ways:

- Primary production from currently producing assets of ~53 million pounds:

- ~9 million pounds per year from Cigar Lake

- ~4.2 million pounds per year from Inkai (counting cut – likely higher in future)

- 8.5 million pounds of inventory on hand as of 09/30/2021

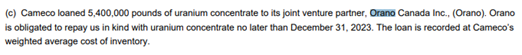

- Cameco is owed 5.4 million pounds from Orano by December 2023 from a prior loan agreement:

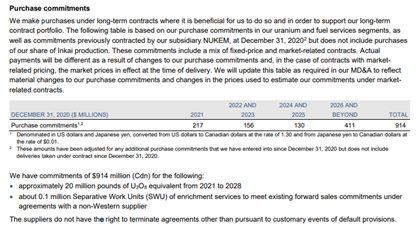

- Contracted purchase commitments – Like many producers at the bottom of the cycle, Cameco has a committed purchase book which we believe were locked in at relatively attractive prices. While they have not updated the figures in detail since 12/31/21, this book entered the year with 20 million pounds of future volume between today and 2028. If you exclude the 2021 commitments and anything after 2025, you still arrive at approximately 6.3 million pounds of contracted purchases between 2022 and 2025.

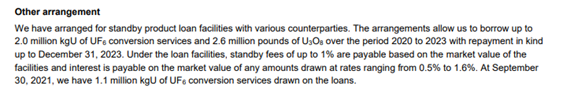

- Standby Product Loans of 2.0 million KgU of UF6 and 2.6 million pounds of uranium:

So some basic math and 15 minutes with the company’s financial statements will show you that they are not actually short much uranium over the next several years. Cameco has approximately ~76 million pounds of uranium (excluding UF6) available to deliver into a ~75-78 million pound contract book – and that’s without McArthur River. That’s also without accounting for other borrowing flexibility they may have with customers at their conversion facility. A couple million pounds over a 4-year period is hardly a massive short in the market. Add their long-term reserves and resources and it is clear that the one thing Cameco wants, more than any other is for prices to rise!

Cameco will be a likely buyer in the future, but to be clear – they want to be. For one thing, their inventories are on the low side, and drawing down on product loans is not in their normal course of business. Anyone who has followed the market for some time knows that the market is healthier with Cameco on the bid – helping smooth out peaks and valleys and ensuring real value is created in their contract book.

Investors can make their own determination about whether Cameco or any other company are good investments – that is not our point. What we are seeking to clarify is whether the company is levered to higher uranium prices, and we think that is crystal clear. Misinformation from poorly informed “experts” can lead to irrational expectations and poor investments – do your own research and approach social media with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Conclusions

- First – we have been bullish the uranium story for some time and remain so – however, we believe understanding market nuances will be more important going forward (while the fundamentals have drastically improved over the past two years, so has the amount of snakeoil being sold to investors).

- The rise of Sprott is undoubtedly positive for the uranium market – we believe producers are the primary beneficiaries of this development in the short term.

- Spot market dynamics are complex and can be difficult for investors to understand. Do not assume that material availability in spot is a bad thing – in the end the uranium market is a zero-sum game with pounds produced, consumed and (now) sequestered. The more this happens, the tighter the market now and in the future will be.

- Utilities should pay attention to how spot market demand may be changing the balance of forward coverage and supply. Do not assume that material on offer today is a sign that future prices will not increase as producer incentives shift.

- While forward contract book replenishment will mean stronger producers through this cycle, we also believe that high quality development projects will see significantly higher through-cycle pricing than they would without Sprott. We continue to think that 4th quartile cost curve assets and exploration “fliers” are a fool’s errand and remain skeptical of high cost or low-quality stories (of which there are many).

Thanks for reading,

Segra Capital Management

[i] Producers have argued for years that a tighter definition of the spot market would actually be a healthy market development and we agree with them. In theory a spot price is meant to show market participants where you can either buy or sell material at any given time. If a barrel of uranium is above ground at a converter, market participants can either buy or sell that material. However, if I see a spot price trade for delivery 9 months out coming from future production, I only have the opportunity to buy those pounds, not necessarily sell them. This asymmetry means that market related contracts priced at “spot” can be misleading. Further distinguishing between pounds in the can and pounds in the ground would increase market transparency and give market participants a clearer view of true spot market depth.

[ii] However, there is a danger for Sprott if funds know they are always open to a block trade. If we were a fund trading in physical, we would simply buy pounds at times the market feels thin, driving up price and increasing momentum – as the market begins to feel heavier, we would approach Sprott for a block trade, gaining liquidity for our position and selling it into the equity market (rinse, repeat). In this case, Sprott will be front-run and buy pounds less effectively than they otherwise would – they key is to keep market players guessing as to when you will and won’t buy pounds (or at least, that’s what we would do).

[iii] We won’t even get into the fact that the equity market, as a discounting mechanism would inevitably look past short term cashflow and earnings volatility if we did have a sustained $100+ market but anyone who’s watched Cameco’s multiples over the past decade knows that to be true.